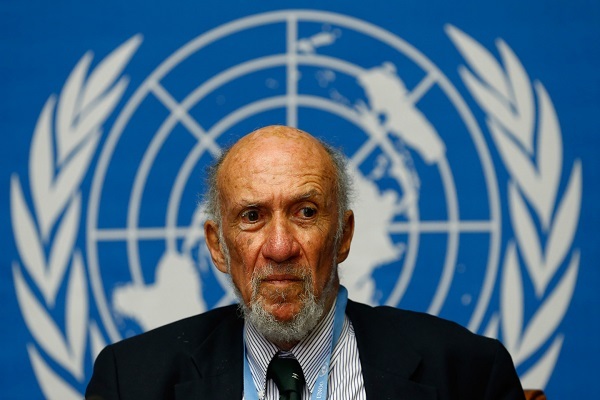

TEHRAN-TABNAK, Jan 18– Richard Falk, the former UN Special Rapporteur for Palestine, says Ayatollah Khomeini was not opposed to the Shah’s entry to the US if it was not coupled with a push for an American intervention.

“Yet future developments included strong anti-Iran pressure from influential foreign policy personalities, most notably Henry Kissinger, and a series moves to sanction and destabilize post-Shah,” Falk, currently a professor of international law at Princeton University, tells the TABNAK in an exclusive interview.

Following is the text of interview:

Q: You visited Iran with an American delegation during the 1979 revolution. You were in Bakhtiar’s office when the Shah fled. What was Bakhtiar’s assessment of the situation?

A: We met with Bakhtiar either the day before or the day after the Shah left the country. When the announcement of the Shah’s departure from Iran occurred. We were in Qazvin at the invitation of several local doctors who had treated injured anti-Shah demonstrators on previous days and were very upset by the severity of the wounds. When the news was first broadcast our hosts in one of doctor’s home he would not believe the radio report, thinking it was a trick to identify the enemies of the Pahlavi palace. As we drove back to Tehran there were many signs of celebration, including posters, horn-blowing, and spontaneous demonstrations.

When we met with Bakhtiar he seemed out of touch with the dramatic realities unfolding in Iran. He exhibited no sympathy for this historic challenge to the Shah. He told us it was only a matter of time before a secular government would be restored. He conveyed an impression of hostility to Islam, enthusiasm for European culture and politics, especially that of France, and viewed his own decision to leave Iran for Paris as very temporary, that is, as soon as counter-revolutionary forces intervened to restore a secular, presumably monarchical government. My recollection is that he discounted the Iranian Revolution by treating it by reference to conspiracy explanations and hence an inauthentic expression of national will.

Q: You have stated that during your meeting with Ayatollah Khomeini, he asked you several times whether the US might return the Shah to Iran. When was this, and were there any signs of this?

A: The meeting with Ayatollah Khomeini took place in one of his last days in Paris before returning to Iran. It was about a week after the Shah had left Iran and was supposedly seeking medical treatment for cancer in the US. In the course of the meeting, which lasted more than two hours, the focal point was the stability and nature of the unfolding revolution. We had to bring the meeting to an end so as to catch our flight back to the US. Ayatollah Khomeini seemed preoccupied with whether the US would seek to restore the Shah to his throne. As I was accompanied by Ramsey Clark, the former Attorney General of the US, it was natural for Khomeini to suppose that Clark would had insider information about US intentions. In fact, Clark was no longer in direct contact with the upper echelons of the US Government.

It was obvious to us that the US covertly facilitated coup in 1953 against the Mossadegh was very much on Ayatollah Khomeini’s mind, and that he feared some form a repeat of that notorious intervention. We were not in a position to give any reassurance except to express the opinion that in the Cold War atmosphere Mossadegh’s radical nationalism and nationalization of the foreign oil company holdings in Iran was probably then more threatening and provocative in Washington than a popular movement with an Islamic agenda. We also acknowledged that this assessment could be wrong due to Israel’s pressure on the US in view of the loss of its positive relationship to the Shah’s government and fear of the Iranian movement anti-Western sentiments.

We had the impression that Ayatollah Khomeini was not opposed to the Shah’s entry to the US if it was not coupled with a push for an American intervention. Yet future developments included strong anti-Iran pressure from influential foreign policy personalities, most notably Henry Kissinger, and a series moves to sanction and destabilize post-Shah.

Q: You also met with William Sullivan, the then US ambassador to Iran. What was his assessment of the situation? Was he not concerned about the future of America’s position in Iran? What is meant by his assessment that the new regime would adopt a strong anti-American approach?

A: Our meeting with Amb. Sullivan was somewhat tense. He greeted us by reminding me that I had testified in the US Congress in opposition to his confirmation because of his earlier role in Laos of directing military operations against the local insurgency from the Embassy in Vientiane.

Actually, Sullivan was more attuned to the revolutionary realities in Iran than Bakhtiar. He appreciated that the victorious movement against the Shah had become ‘the only game in town’ and encouraged the Carter government in the US to accept this fait accomplis and move to normalize relations by recognizes as legitimate the new governing authorities in Tehran. Unfortunately, Brzezinski, Carter’s National Security Advisor, remained deeply attached to the Shah’s government, and opposed successfully Sullivan’s advice. We later learned that our on-the-record meeting with us effectively ended Sullivan’s career as a diplomat, which up to that point had been promising.

In retrospect, I believe that if Sullivan’s approach to the Iranian Revolution had prevailed in Washington the whole trajectory of subsequent relations between the two countries might have been different. In Iran, the theocratic influence might have been far more limited, and the moderate technocrats and humanistic leaders such as Bani Sadr could possibly have led Iran to a secure and prosperous future. In the US, the anti-regime stance taken to the Islamic Republic would have been marginalized by mutually beneficial economic relations. Of course, this ‘road not taken’ scenario was always vulnerable to Israeli pressures, which might have been intense no matter how the new Iranian government behaved. When we met with Ayatollah Khomeini, he made clear that Israel was an adversary as distinct from the Jewish minority in Iran, which he pointedly said, “If Jews in Iran do not involve themselves with Israel’s policies, they would be welcome in Iran as an authentic religion.” He added, “It would be tragedy for us if they left.” This contrasted with his views on the Bah ’ai community, which he said “was not an authentic religion, and they have no place in Iran.”

Q: After your meeting with Sullivan, you announced that before the1979 revolution, the US embassy had prepared 26 different scenarios regarding the threat to the stability of the Shah’ regime and the situation in Iran, but none of these scenarios mentioned or predicted a threat to the government from Islamic groups. What was the reason for this?

A: I have no special knowledge on this. I suspect that Sullivan told us this to let us know how clueless even US intelligence sources were about the play of forces in Iran and the strong Islamic orientation of the Iranian masses. In a sense US preoccupations were confined to three concerns: 1) the containment of the Soviet Union and Marxist-oriented national movements; 2) the protection of US and allied foreign economic interests; 3) reliable access to Gulf oil and gas reserves that depended on West-friendly government in the region.

The 26 scenarios flow from this kind of misleading threat perception from the perspective of US interests and a sense that cultural values and populist alienation were of little or no political relevance.

As the Soviet Union was anti-religious, there was a tendency at that time to disregard religious anti-imperial orientations, and in particular Islamic potential potency. Iran could have been a wakeup call, but the situation was badly mishandled by Washington. US Islamophobia did not arise seriously until 2001 in reaction to the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon.

Q: Your meeting with Ayatollah Khomenei was at Noufal Chateau in France. What were the most important topics of your conversation and what vision did you present of the future government of Iran?

A: I would say the most important topic from Ayatollah Khomeini’s perspective was the issue of possible US engineered counterrevolution and intervention to restore the Shah for a second time to power in Iran.

From our perspective, it was to learn as much as we could about Khomeini’s vision of the future of the Iranian Revolution. Several time the ayatollah reminded us that it was not an Iranian Revolution, but should be properly identified as an Islamic Revolution, with implications for the future governance of Iran and its relations with the Middle East. In this regard Ayatollah Khomeini made clear his hostility to dynastic rule in Saudi Arabia, explicitly saying it was not better than Iran’s oppressive regime under the Shah.

We were also interested in Ayatollah Khomeini’s own future plans in Iran, whether they included ambitions to be the political leader in the post-Shah period. He told us he planned to resume a religious life in Qom after his return to Iran, and added that he only entered politics because in his words ‘there was a river of blood between the people and the government.’

I have always wondered whether these plans reflected some failure on the part of the Ayatollah to appreciate what an acclaimed leader of the revolution he had become. In fact, after returning to Iran he did for some months reside in Qom until he moved to Tehran to assume leadership of the government and advocate of Islamic governance elsewhere in the region. Whether this leadership role was always part of his personal vision or a reaction to his popularity or the widespread sense that the semi-secular and technocratic first wave leadership of post-Shah Iran was too weak to uphold the ideals of the revolution or some combination of all of these factors.

Q: Some believe that one of the reasons for the collapse of Mohammad Reza Shah's regime in Iran was Carter's pressure. This is despite the fact that, according to documents, Carter had told the Shah that he would support the army against the revolutionaries. What is your opinion?

A: My strong impression is that Carter, possibly under the influence of Brzezinski, was unwavering in his support of the Shah. From the time he chose to spend his first presidential New Year’s Eve to his publicized interruption of the Camp David Peace talks between Egypt and Israel to commend the Shah for a show of force against peaceful demonstrators in Jaleh Square, Carter departed from his human rights agenda to show his support and affection for the Iran’s royal family. Our meeting with Sullivan, and my contact with the State Department during the 1979-80 hostage crisis, confirm this impression that Carter never abandoned support for the Shah, although some right-wing politicians criticized Carter for not directly intervening to save the regime of a close ally by way of NATO or otherwise. I believe this option was explored, including by having a NATO general come to Tehran and confer with Iran’s military leadership, but was discouraged from expecting any military support for crushing the revolutionary movement by late 1978.