Rouhani Could Lose Iran Presidency: Seven Charts Illustrate Why

Iran’s more historically reliable opinion polls indicate President Hassan Rouhani is likely to win his bid for re-election on Friday. Yet his conservative challengers have put up a stronger fight than many expected, attacking his government’s economic record and accusing him of failing to improve living standards for the poor.

According to Bloomberg, if there is to be an upset -- Rouhani would be the first president in the 38-year history of the Islamic Republic not to win when seeking a second term -- the following charts illustrate some potential causes.

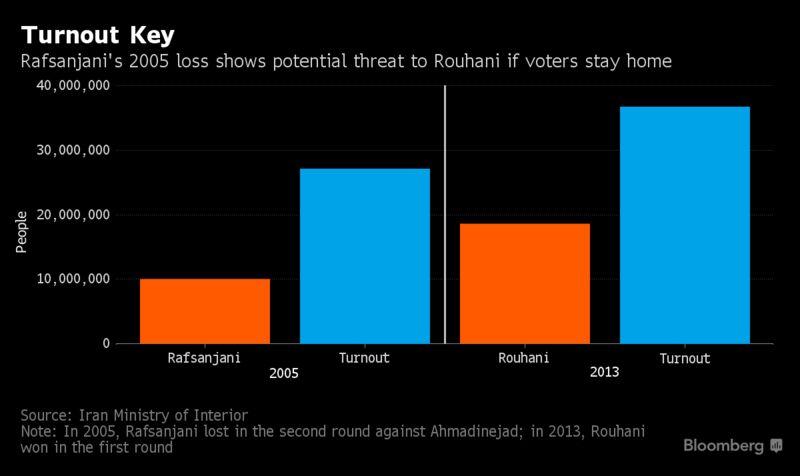

Voter Motivation

Rouhani’s supporters are worried about voters staying home on election day. The president is a pragmatic regime stalwart, and a victory will hinge on persuading enough Iranian liberals, known as reformists, to back him. That’s something the late Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, another pragmatic regime veteran, failed to manage in 2005, when low turnout handed the election to populist conservative Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Reformists came out for Rouhani in 2013, as did many rural voters looking for economic improvement. But will they again?

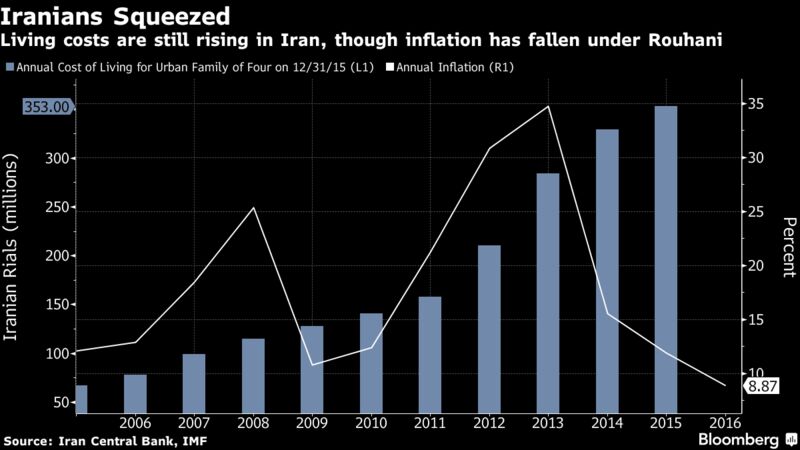

Rising Costs

Rouhani has campaigned on his economic record, and especially his government’s achievement in bringing down inflation from above 30 percent in the later Ahmadinejad years to about 9 percent now. But that means the cost of living is still going up, and while real wages have risen for most Iranians, it’s not been enough to compensate.

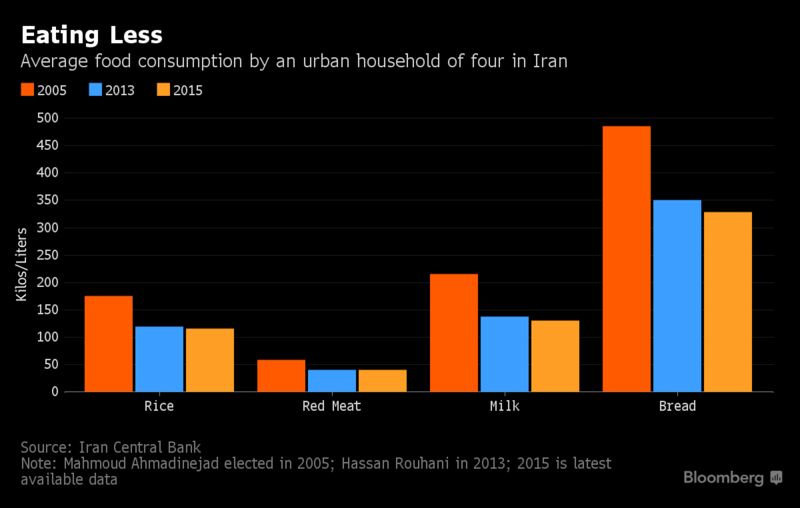

Food Pressure

Stretched consumer finances mean the average Iranian household is now eating less meat, dairy products and other basic foodstuffs than they were in 2005. That’s a problem for the government, which based its support for the nuclear deal with world powers in 2015 on the lifting of sanctions and an expected boost to living standards.

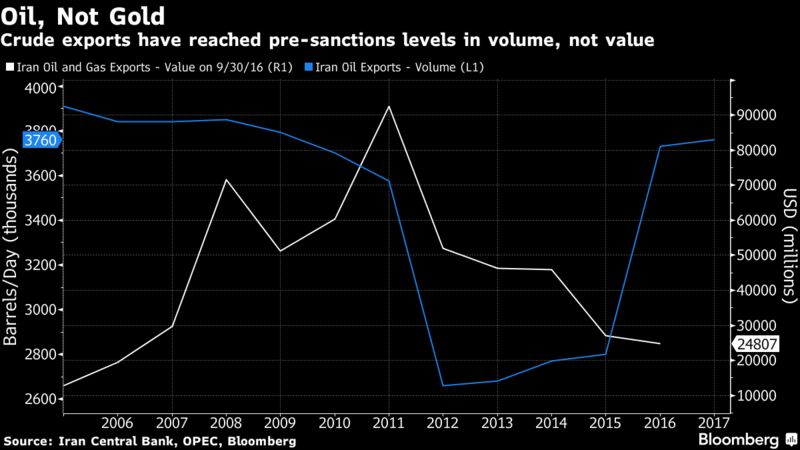

Crude Price Slump

The nuclear deal, which took effect early last year, has allowed Iran to double its oil exports -- with volume returning to its pre-sanctions level. Unfortunately for Iran, global oil prices have collapsed since Ahmadinejad was able to tap into as much as $92 billion of crude export revenue to fill government coffers and fund subsidies. Current revenue is lower than it was during the deepest production cuts of the sanctions era, giving Rouhani less cash to redistribute or invest.

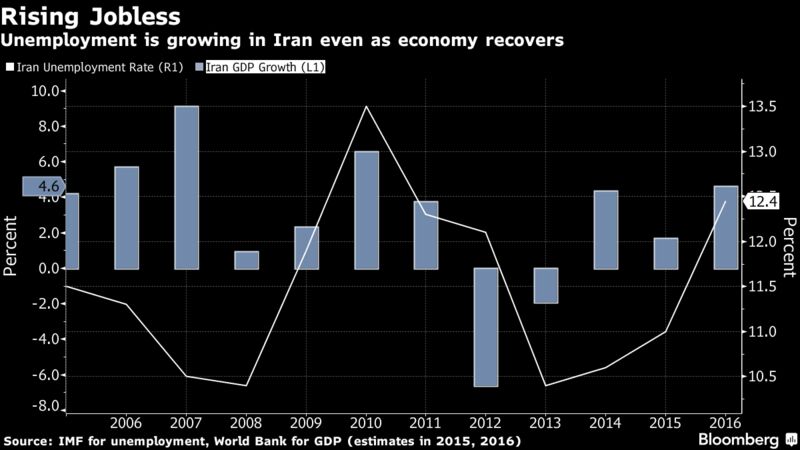

Out of Work

Rouhani has also stabilized economic growth at about 4 percent -- a far cry from the 6.6 percent contraction the year before he took office. That hasn’t yet translated into more jobs -- unemployment has actually been rising in recent years -- in large part because the key non-oil economy hasn’t kept pace.

Non-Oil Flop

Iran’s non-oil economy, the main engine for large-scale job creation, contracted in 2015 and barely grew last year. That’s partly because, even as the inflation rate fell to single digits, competition among banks to attract deposits have kept real interest rates high. In February, the International Monetary Fund recommended "urgent action” to recapitalize and restructure lenders.

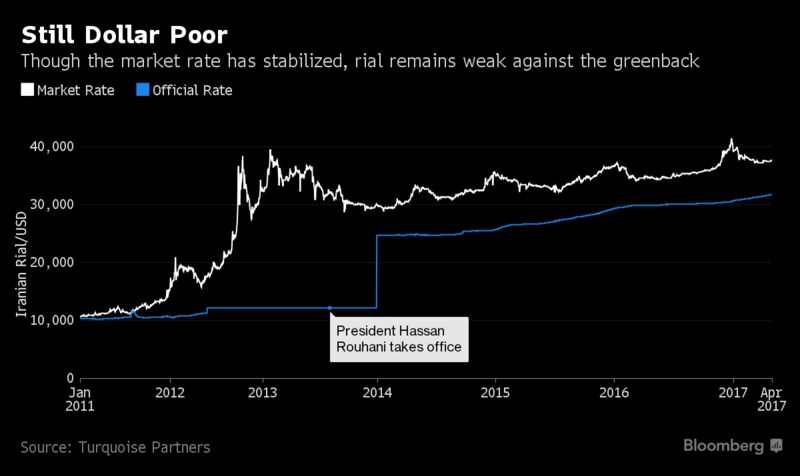

King Dollar

Whatever Iran may think of the country it dubs the Great Satan, it certainly likes the U.S. currency. For Iranians, the rial’s exchange rate to the greenback has always been an important indicator of how the economy -- and they themselves -- are doing. Under Ahmadinejad, the rial crashed to almost 40,000 per dollar from under 10,000 in unofficial trading, dramatically reducing purchasing power. While Rouhani has brought the official and street rates more into alignment, and stabilized the official rate, the rial hasn’t recovered its lost value.

سایت تابناک از انتشار نظرات حاوی توهین و افترا و نوشته شده با حروف لاتین (فینگیلیش) معذور است.